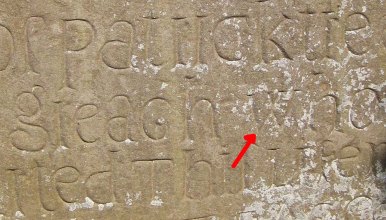

Pitkin headstone, 1694 (vandalized), Hartford, CT. Note the VV style W. Photo by author, 2016.

Inscribed text is something that I’ve been passionate about studying ever since my first field school as a little baby undergraduate student. Recording gravestones in a rainy July in Ireland, I pieced together fragments of words that no one had read out loud for decades and recorded them onto my forms, creating a record once more for a nearly-erased gravestone. In doing so, I became fascinated by the way that letter forms evolved and were adapted through history, from inscribed letters in stone, to calligraphy, to typeface for printing presses which has become our digital text today!

Several years ago I conducted a project funded by the P.U.R.E Grants through the University of Calgary to explore the way in which letters erode from the face of gravestones, during which I spent a lot of time sitting in the rain with my waterproof notebooks, drawing letters using a hash-line system I developed to represent different stages of erosion. It’s a whole thing. The paper which resulted from this project is currently in peer-review, and I wanted discuss in part, one of the aspects of the project in conjunction with my recent interest in ritual protection marks. In this case, the letter W, and their use in inscriptions and as protective markings.

William de Wermington, c. 1330, Crowland, Lincolnshire. Image from the Monumental Brass Society, 2002.

First, lets discuss capital letters. Within my previous research area at least, the VV style W went out of fashion (i.e. regular useage) on gravestones by the mid-1700s. This doesn’t mean it doesn’t appear after that date, but it was less common for sure! I like to refer to it as an ‘archaic W’. The letter W is not present in Latin, but evolved in written form as ‘VV’ or ‘uu’, as there was no letter in the Latin alphabet to represent the Old English sound /w/. These characters did not come together to form an archaic W for years, with early printing machines sometimes still using two uu’s or vv’s to represent the letter before a ‘w’ block was made for them (Oxford Dictionary). The examples we are going to look at are all capital W’s, as incised lower-case letters in stone were fairly rare prior to the early 1700s.

On mortuary sculpture (monuments, slabs, gravestones, etc), we see something a little different. While brasses from the pre-Reformation era often bore text in a ‘Gothic’ script which included a form a ‘W’ which was created by v-like strokes, other inscribed slabs such as this example dating to 1330 displays a capital W made of two overlapping ‘V’s, a step toward the modern letter from the older ‘VV’ side by side. A modern example of that particular out-of-use W can be seen on the 2015 film ‘The VVitch’.

Similarly, text in the form of written documents often displays a ‘w’ in lowercase which more closely resembled the modern version than the inscribed version, suggesting this practice may only have existed within inscribed lettering. This is something which I would be very interested in reading more about, if anyone has any resources on the development of English letters! So far I haven’t found any written examples of a VV crossed over W in handwriting, but if you know of a bunch, send them over?

- Sir. David Kirke, 1629

- 1629, regarding Ferryland

- George Calvert, 1629

This ‘archaic W’ made of overlapping ‘v’s can be seen widely on graves from the 17th century as well, in both the British Isles and New England. Their use in New England continues in some cases throughout the 18th-century as well, and could indicate a fossilization of certain aspects of text in the New England literary culture. This fossilization of tradition can be seen with other aspects of culture, such as the continued use of ritual markings in public ways, while these markings were taken out of public view in many cases in the UK and moved from venues such as the church to inside the home.

Cross gravestone, northeast Ireland, 1687. Note the archaic W’s, capital letters, and simplistic serifs. This is a stereotypical example of the archaic roman script. Photo by author, 2012.

So the archaic W was used on gravestones for ages, what does that tell us? That it evolved from some u’s and v’s, of course. But what about it’s continued usage in areas like New England, long after early and modern roman scripts had been developed? I have some thoughts on that!

Pitkin footstone, 1694, Hartford, CT. Note the archaic W beside a more elaborate P. Photo by author, 2016.

If you exist within the archaeology twitter community, you might have seen people (+me) posting about ‘Medieval Graffiti’ from time to time: pictures of hexfoils, pin wheels, and other marks carved into medieval churches as a part of common ritual during the medieval period. These designs were simple and could be carved into stone or timber with a pair of sheers or a knife blade, and were designed to protect the object or space they were carved into from evil. In many different parts of the world, hexfoils were even carved into gravestones (Easton 1999), as you may have read about on this blog already!

(if not, check out –> THIS <– previous post!)

This was potentially to protect the soul of the deceased, or even visitors to the grave, and was a visible continuation of the protective mark tradition out in the open once more, in a very deliberate way.

In the UK, protective marks used to be carved openly in churches, but with the Reformation came a removal of previously accepted folk ‘magic’. Of course, this did not mean that people stopped carving the symbols, but simply that they were less obvious, less public. This practice is very prominent in New England right up into the 19th century, both within the home and on gravestones. Common household symbols took the form of hexfoils, crosses, circles, and letters such as M (inverted overlapping V’s) and W (archaic W).

17th-century hearth beam, Winston, England. Note the W’s combined with a P, along with initials of the home owners. Image from Easton 1999: 25.

The overlapping ‘VV’ mark is often suggested to be the initials of ‘Virgo Virginum’ of the Virgin of Virgins, and if it was written as an ‘M’ it could also suggest ‘Maria’, again the Virgin Mary in the medieval period, but it is very likely that the meaning evolved away from the obvious religious connotation to mean more of general protection or good luck later on (Champion 2015: 55). It was very easy to carve an archaic W or ritual M with a knife blade of any kind, and it is common to find these marks above the doorways, windows, and hearths of houses from as early as the 16th century in the UK and the 17th-18th century in New England (or possibly later, there are several examples of hexfoils on 19th-century gravestones in MA). These symbols were used in churches prior to the Protestant Reformation as well.

What I find particularly interesting is the letter W being deliberately drawn as two overlapping ‘V’s’ to form this protective marker, and that letter style being used on graves. On the above example of the Pitkin footstone, the carver created a very elaborate P while leaving the W as two simple V’s, reminiscent of the protective marks being used around that period to protect from ‘witchcraft’, specifically.

Furthermore, if the predecesors of the modern W were ‘VV’ or ‘UU’ then the logical next form of that letter would be those earlier characters connecting, not overlapping in the way that they do for the ritual symbol. You could suggest then, that the overlapping ‘VV’ mark that makes up the archaic W when used in inscribed text, is a fossilization of the nature of the symbol itself, or even a deliberate use of the symbol resembling a letter and being placed on gravestones.

Gravestone in northeast Ireland showing mainly early roman lettering, with the exception of the archaic W and lowercase ‘handwriting’ style ‘s’. Photo by author, 2012.

There are examples of the archaic W being used on gravestones after the rest of the script being used has evolved beyond the archaic form of roman, such as this example from Ireland, dated 1776.

Of course, W is also a letter as much as it was used as a protective symbol in the late-post-medieval period / colonial period, and this could simply be a case of it being the easiest way to carve the letter, or people thought it looked interesting, or a slew of other reasons that make just as much sense. But it could also have kept being used in this form because it did double as a protective mark in some instances. Much the same as masons using the W to mark their stones as nothing more than a mason’s mark, but them having potentially chosen that make because it was also a protective mark (Champion 2016), so too could this extended use of the archaic W that we see on words inscribed in stone text have been used because people knew it was also, or had previously been, a protective mark.

Archaic roman W on the largest of the Ferryland gravestone pieces. This dates to the early 1600s, and is within the correct timeline for both protective markings and the script style. Photo by author, 2016.

Of course, all of this is speculation without more evidence on the subject, but it is something I have been pondering over for some time now. I like the idea of people integrating a protective mark into the writing on the grave markers of their loved ones, even more so if they were doing it after the Reformation as a rebellious means of continuing a centuries-old tradition of ritual protective marks. This could simply be a case of a letter being similar to a protective mark, and that is all, but it is definitely something to think about, especially in cases where all other letters in an inscription have changed to a different script style except the W.

The use of folk traditions and protective marks is very interesting, and definitely something I’m looking to explore more on this blog now that I have some time to think about things other than my thesis a little bit!

Works Cited:

Champion, M. 2015. Medieval Graffiti: The Lost Voices of England’s Churches. Ebury Press: London.

Champion, M. 2016. Marking the Stone: Medieval Mason’s and a bunch of bankers… (blog post) Demon traps, Spiritual Landmines, and the Writing on the Walls. Available online at: http://medieval-graffiti.blogspot.ca/2016/06/marking-stones-medieval-masons-and.html

Monumental Brass Society. 2002. (image) Crowland Incised Slab. Available online at: http://www.mbs-brasses.co.uk/page426.html

Easton, T. 1999. Ritual Marks on Historic Timber. Weald & Downland Open Air Museum Journal, Spring 1999: 22 – 35. Available online at: http://www.wealddown.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/1999-04-WDOAM-Magazine.pdf

Pingback: Canadian History Roundup – Week of August 20, August 27, and September 3, 2017 | Unwritten Histories

November 6, 2017 at 3:10 pm

Hi, very interesting!

I am investigating some graffiti incised into brickwork (WR 1775) as a means of dating a building (dodgy ground i know).

But… the brick in question is above convenient height within the elevation and, of most relevance to this blog entry, the W is formed in two interlocking Vs (with serifs).

Can i send you the image perhaps?

Guy

LikeLike

November 17, 2017 at 1:27 pm

Hi there,

That sounds really interesting, I’d love to see a photo of it! It could be graffiti, or perhaps even a mark from whomever made the brick in the first place.

Cheers,

-Robyn

LikeLike